x = 5

y <- 8

z <- x+y

zWeek 10 - Introduction to R

Which programs you should download and install

- R programming language (required) (the link for CRAN project).

- RStudio (Not required but strongly recommended) (the website of RStudio)

What the R part of the course will cover

In the following two weeks you will learn:

- Introduction to R.

- Data types in R.

- How to import data in R.

- Checking summary stats and making exploratory data analysis with R.

- Using

dplyrto manipulate data with R. - Using

ggplotfor data visualization with R.

What is R?

- R is a suite of software facilities for:

- Reading and manipulating data

- Computation

- Conducting statistical data analysis

- Application and development of Machine Learning Algorithms

- Displaying the results

- R is the open-source version (i.e. freely available version - no license fee) of the S programming language, a language for manipulating objects.

- Software and packages can be downloaded from the link for CRAN project

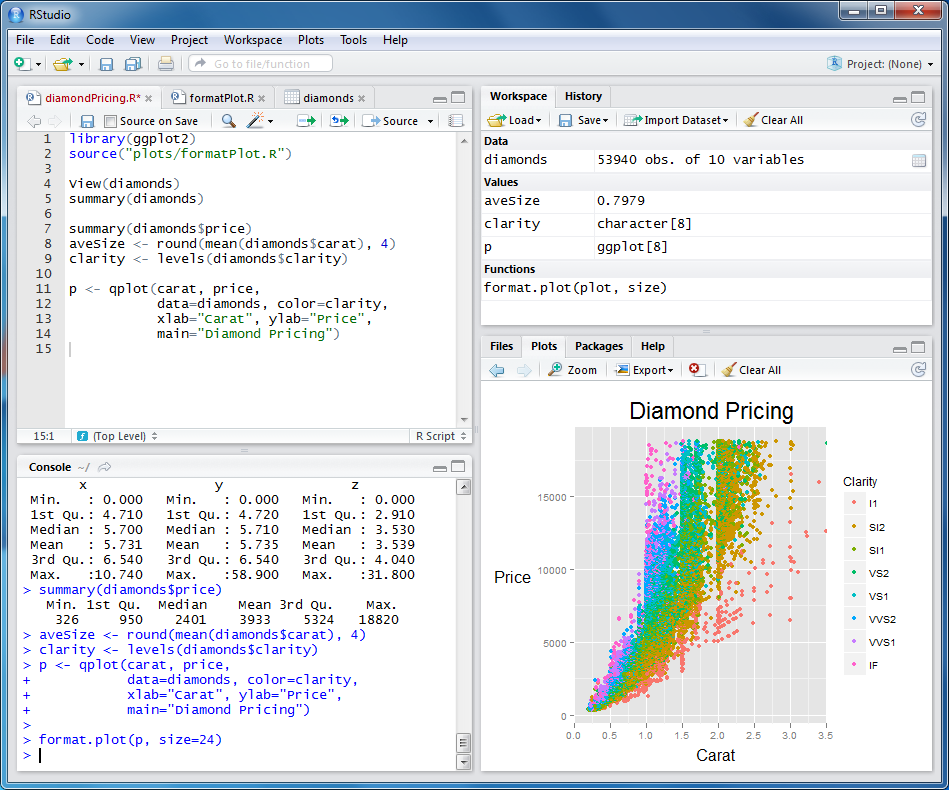

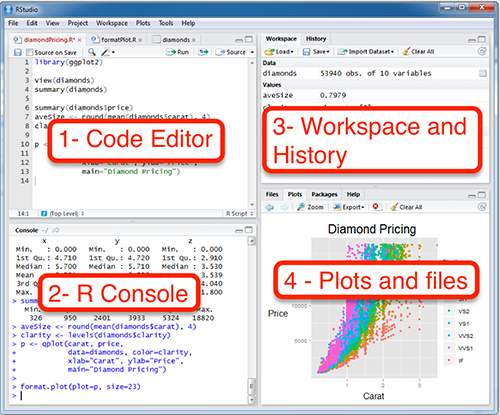

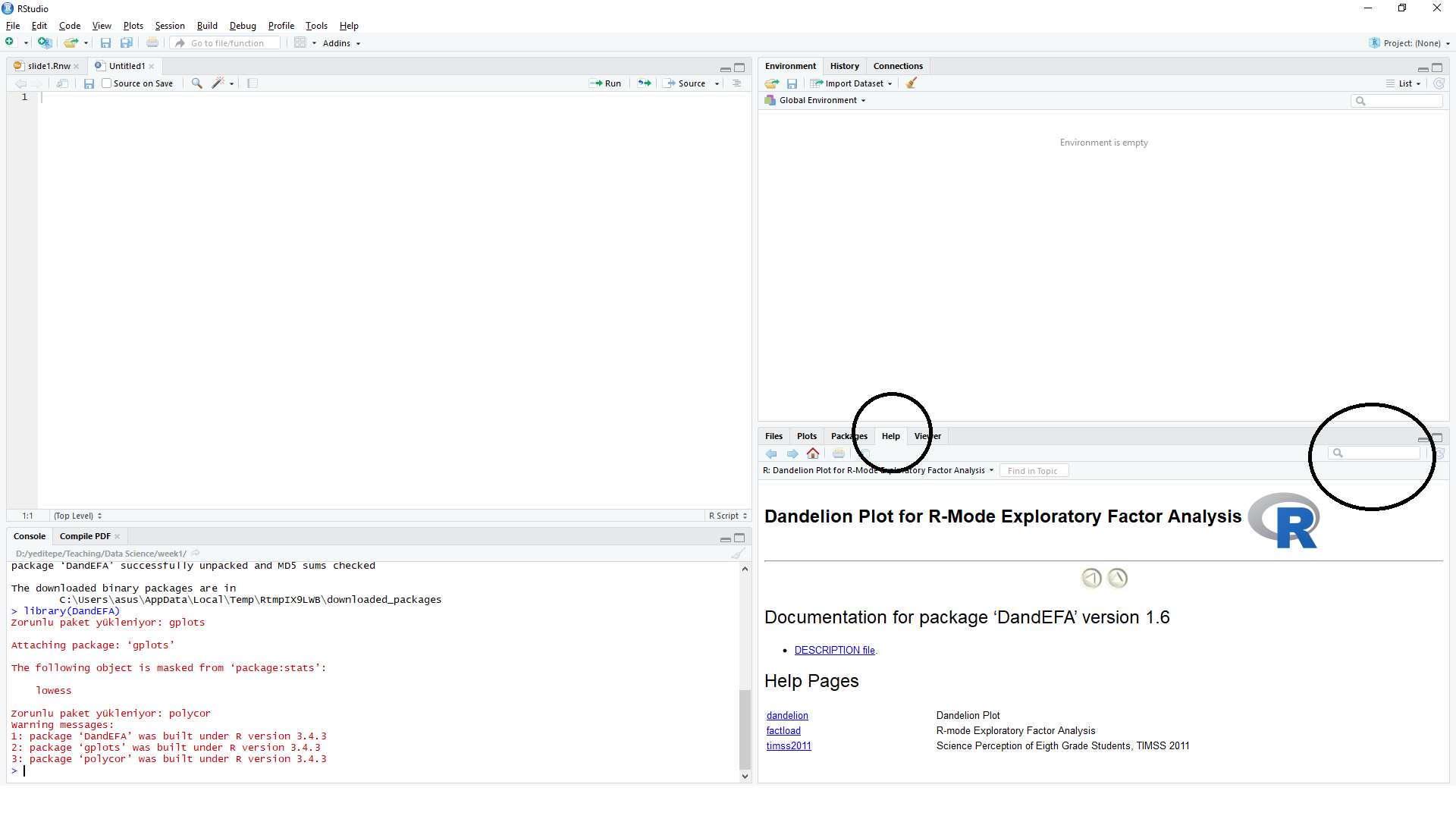

RStudio

- The R Console by itself is not very interesting and useful. A tool named RStudio is designed to use R more efficient and easily.

- RStudio can be installed after installing R.

- RStudio won’t work without R. R has to be installed on your computer.

- You can think RStudio as an upgrade of R, on visual and functionality terms. It doesn’t add anything that R cannot do.

- RStudio can be downloaded from the website of RStudio

- RStudio have 4 main parts:

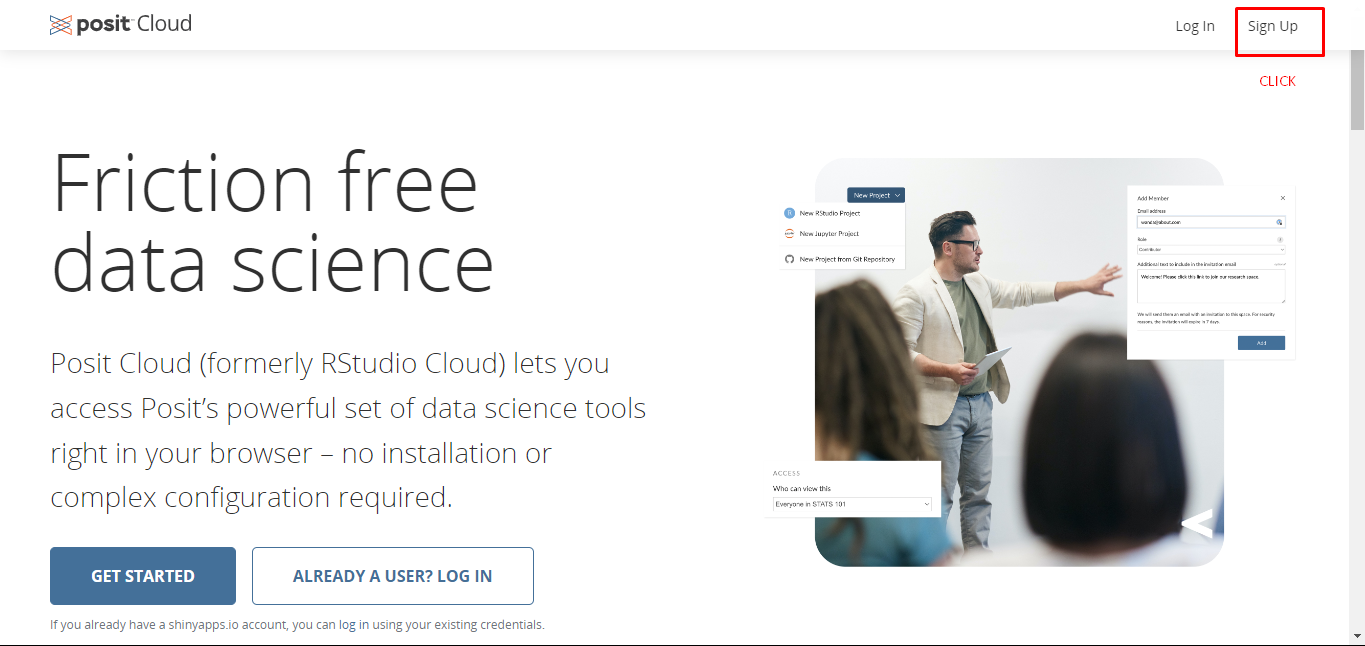

Using R and RStudio from Posit Cloud

If you are a beginner at R and will only use it for the lecture then you may not want to install it into your computer.

A great alternative for this is to use Posit Cloud.

Posit is the company that is the founder of RStudio and provides a cloud solution for using R and Rstudio.

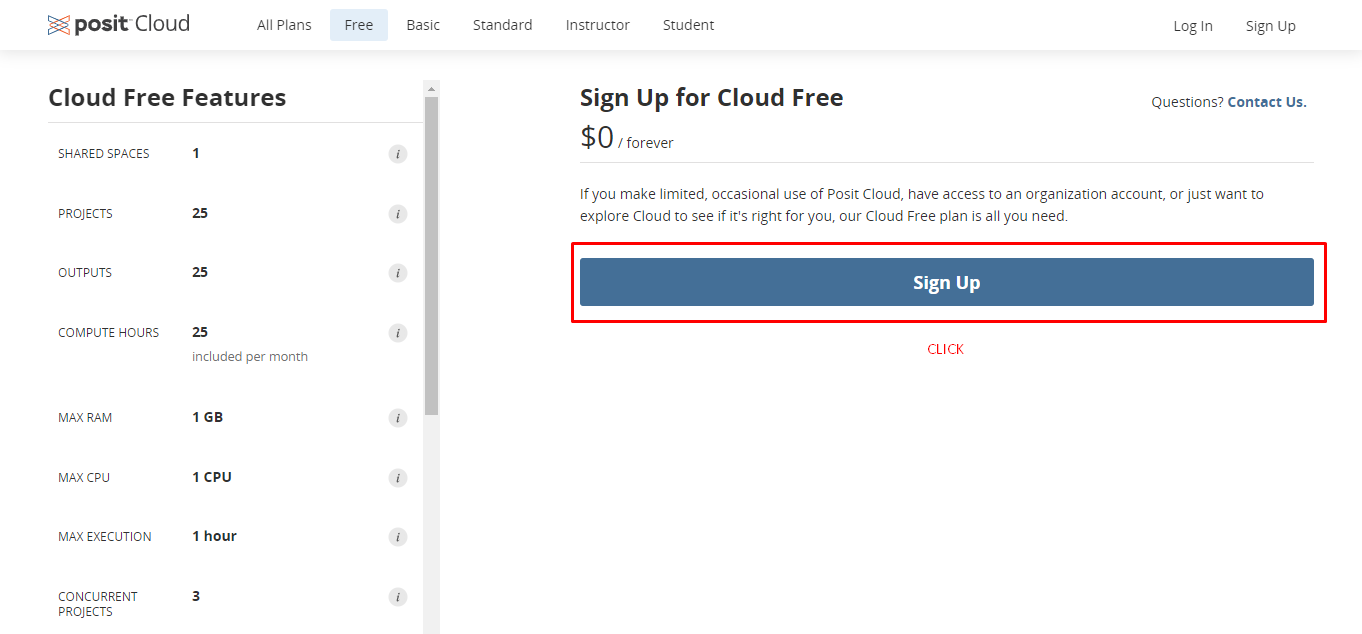

First, go to the website of Posit

Click Sign Up at the upper right part of the page

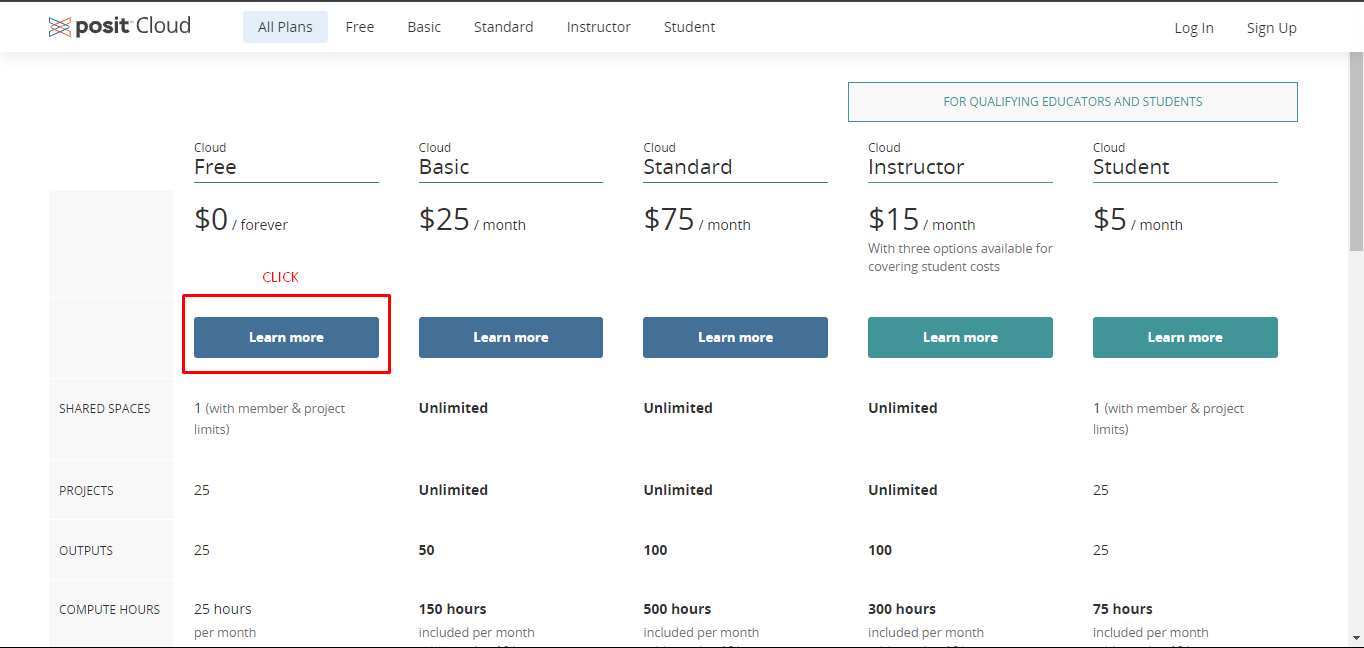

- Then, select the free plan and click Learn more.

- The Free Plan gives you 25 hours of computing time per month which should be sufficient for this course.

- If you ever think that you are going to exceed the limit you can always download and install R and RStudio to your computer for free.

- Click Sign Up at the next page.

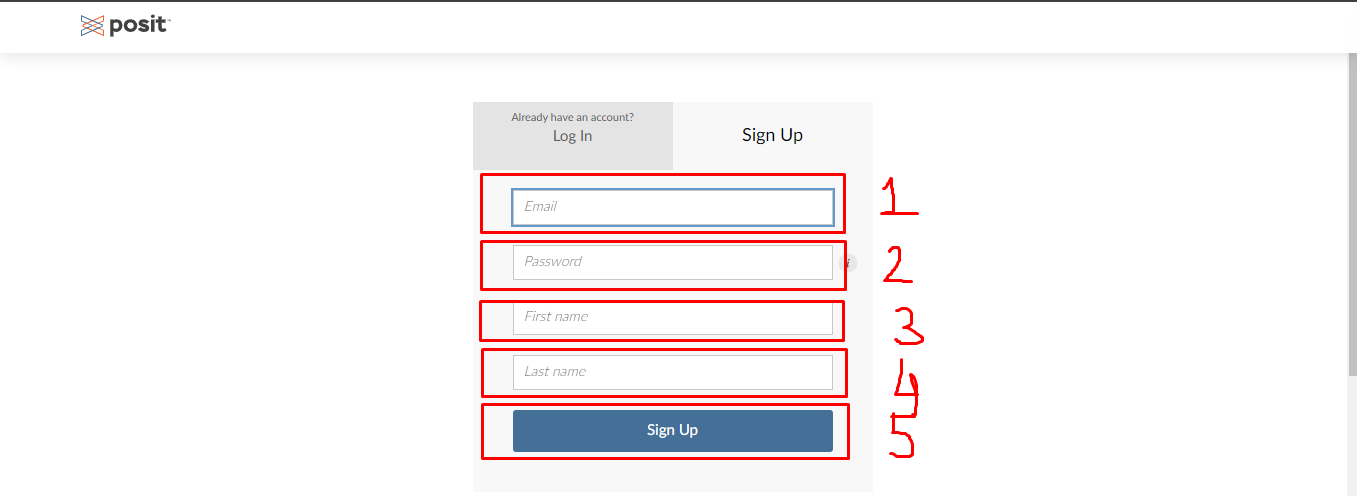

- Enter your e-mail, a password, your name and your surname to register to posit cloud.

- After registering and possibly confirming your mail address, you can login with your e-mail and password.

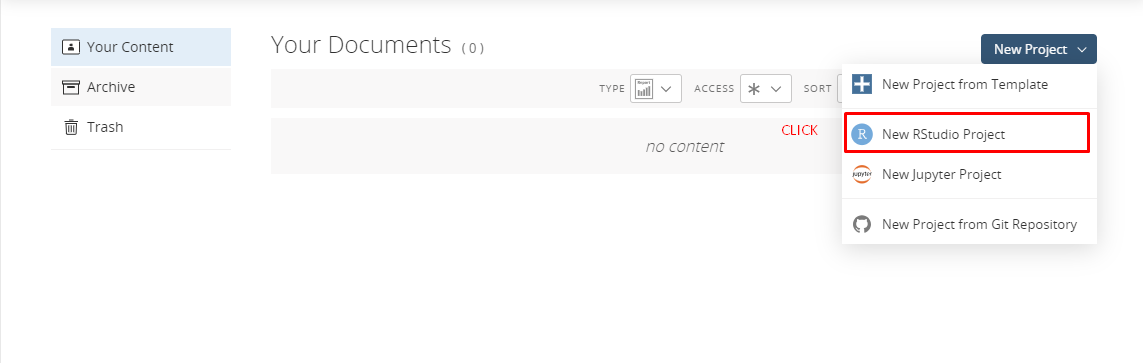

- You will encounter the following page when you successfully login to the Posit Cloud.

- Select New Project and New RStudio Project from the upper right buttons.

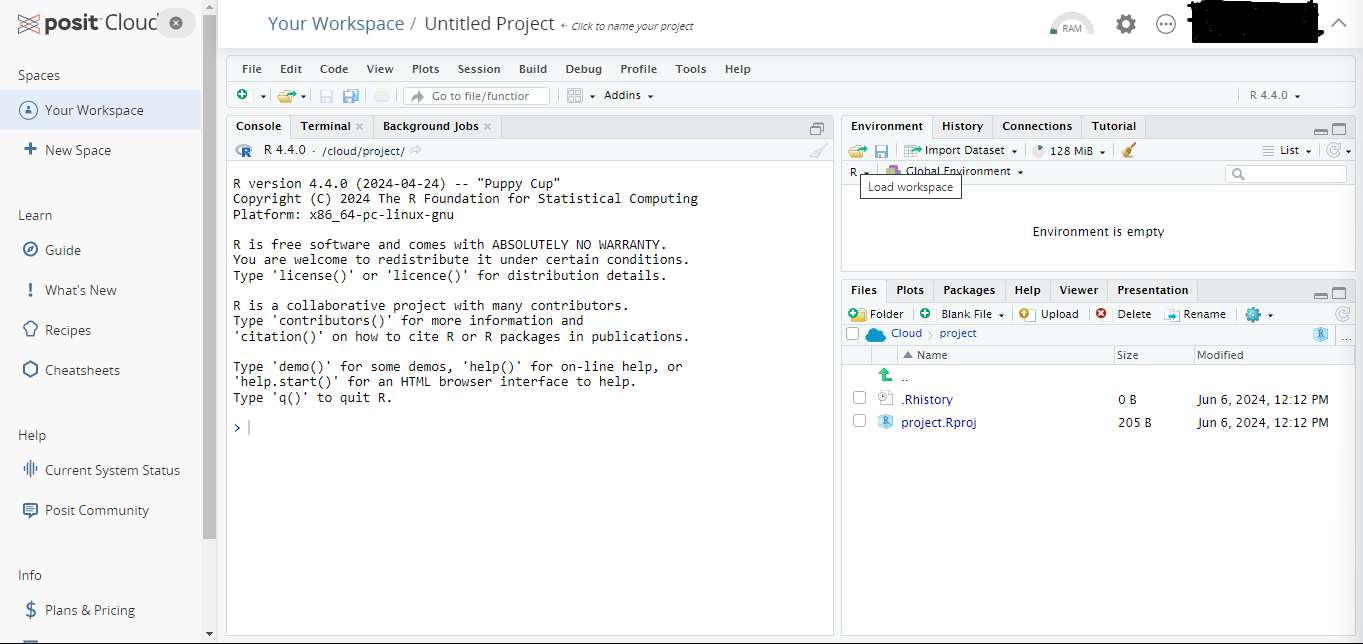

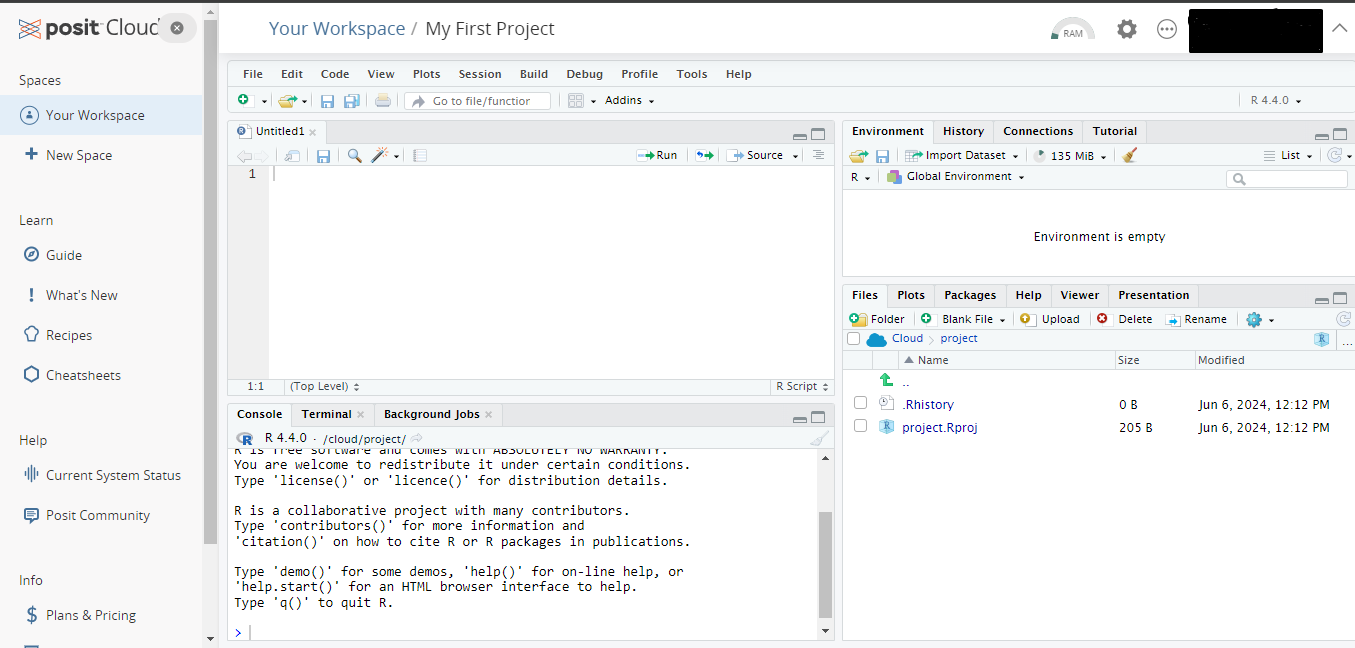

- After a short period of deployment time, a fresh Rstudio will open as in the following picture.

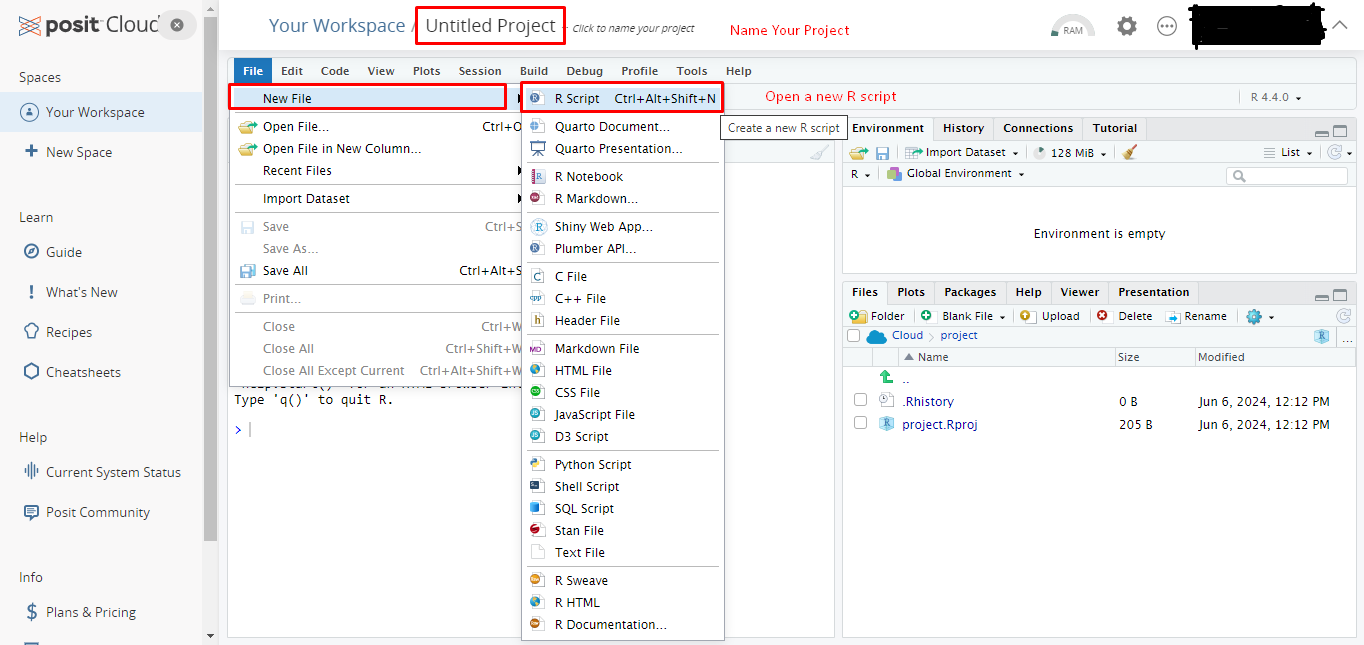

- Give a new name to your project and open a R script to work on from the menu File \(\rightarrow\) New File \(\rightarrow\) R Script.

- Now you can start to use RStudio in cloud and make your computations.

Advantages of R

- Open Source:

- There is no clear difference between user and developer.

- A unique solution for the given problem can be constructed.

- You are not limited to pre-defined options by a fixed user interface as is common in proprietary software.

- Open source also allows to use the program freely without spending any money.

- Flexibility:

- Gives access to the source code, allows to modify and improve it according to the needs.

- Ability to further developments and capacity increase with tools like RStudio and Shiny.

- New packages to solve a certain problem is consistently added to the R repository.

- Ability to produce reports in PDF and HTML format.

- Community:

- R has a lot of material in online platforms, in books and in courses.

- A lot of information can be found via Q&A websites, social media networks, and numerous blogs.

Some useful websites to get help

Typically, a problem you may be encountering is not new and others have faced, solved, and documented the same issue online.

- The following resources can be used to search for online help. Although, I typically just google the problem and find answers relatively quickly.

- RSiteSearch(“key phrase”): searches for the key phrase in help manuals and archived mailing lists on the R Project website at http://search.r-project.org/.

- Stack Overflow: a searchable Q&A site oriented toward programming issues. 75 % of my answers typically come from Stack Overflow questions tagged for R at http://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/r.

- Cross Validated: a searchable Q&A site oriented toward statistical analysis. Many questions regarding specific statistical functions in R are tagged for R at http://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/tagged/r.

- R–seek: a Google custom search that is focused on R-specific websites. Located at http://rseek.org/

- R -bloggers: a central hub of content collected from over 500 bloggers who provide news and tutorials about R. Located at http://www.r-bloggers.com/

- ChatGPT obviously.

Basic Calculations and Defining Objects in R

- You can either write a code directly into the console or you can use a script.

- Using a script is more efficient. Because it is easier to write modify and save a R Code in a script.

- Open a script with File \(\rightarrow\) New File \(\rightarrow\) R Script or you can use shortcut Ctrl + Shift + N

Objects

- R works by creating objects and using various functions calls that create and use these objects. For example;

- Vectors of numbers, logical values (TRUE and FALSE), character strings and even complex numbers.

- Matrices and general n-way arrays

- Lists - arbitrary collections of objects of any type; e.g. list of vectors, list of matrices, etc.

- Data frames - a general data set type

- functions (yes even functions are objects)

Defining Variables in R

- R is case sensitive !!!

Basic Math in R

43 + 35 # addition43 - 35 # subtraction12 * 8 # multiplication100 / 8 # division2^4 # power100 %% 8 # remainder100 %/% 8 # dividentLogical Comparisons in R

5 < 82 + 2 == 5T == TRUE3 * 3 == 93 * 3 != 83 * 3 != 9Functions

Functions are special commands that are designed for a particular purpose.

For example

sum()gives the sum of a numerical values,sqrt()takes root of a number etc..Functions are always followed by a

(). Inside the()most of the functions take some special values called arguments.Lets look at the

helppage for thesqrt()function.

?sqrt{r, out.width = "80%", fig.asp=.75, echo=FALSE, fig.align= "center", fig.cap="Help Documentation for sqrt() function"} knitr::include_graphics("./figures/help_sqrt.png")

sqrt()function only takes one argumentxwhich is either a single number, or arrays of numbers.

sqrt(8)sqrt(c(1,4,9,16,25))- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Lets look at the

helppage for thesum()function.

?sum{r, out.width = "80%", fig.asp=.75, echo=FALSE, fig.align= "center", fig.cap="Help Documentation for sum() function"} knitr::include_graphics("./figures/help_sum.png")

- According to the help file the usage of function is

sum(..., na.rm = FALSE) sum()function takes two arguments....numeric or complex or logical vectors.na.rmlogical. Should missing values (including NaN) be removed?

- The second argument

na.rmhas a default value ofFALSE. A default value means that if you don’t specify a value, it will take the default value, hereFALSE.

x<- c(6, 8, 10, 12, 14)sum(x)sum(x, na.rm = FALSE)sum(x, na.rm = TRUE)y<- c(6, 8, 10, 12, NA)sum(y)sum(y, na.rm = FALSE)sum(y, na.rm = TRUE)z <- c(T, T, F, F, F, T, T)

sum(z)Packages

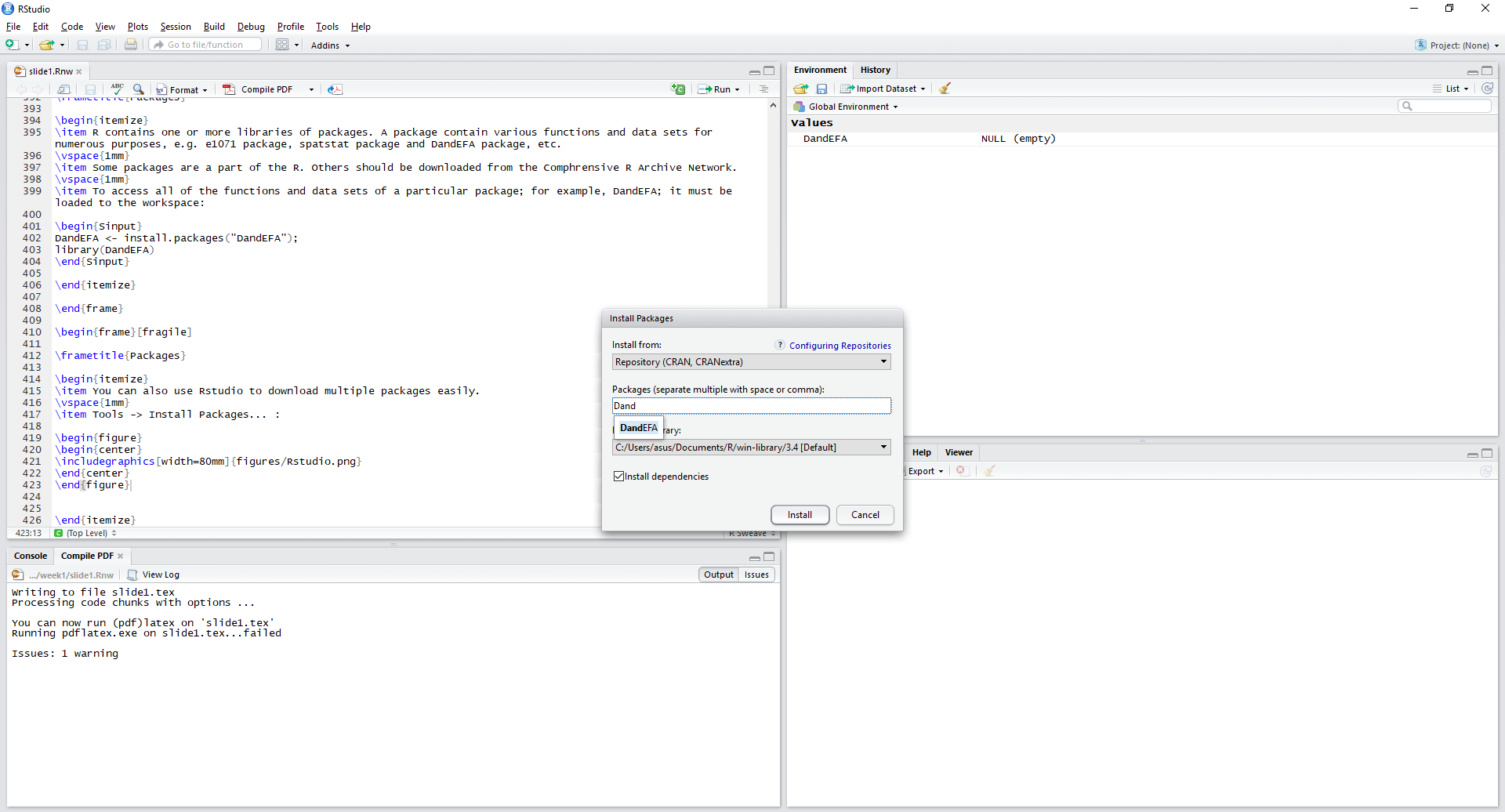

- Some functions are not contained locally in R. They are called packages and they should be installed when needed.

- R contains one or more libraries of packages. A package contain various functions and data sets for numerous purposes, e.g.

e1071package,spatstatpackage andDandEFApackage, etc. - Some packages are a part of the R. Others should be downloaded from the Comphrensive R Archive Network.

- To access all of the functions and data sets of a particular package; for example, DandEFA; it must be loaded to the workspace:

# install.packages('DandEFA')library(DandEFA) # Buy you have to call and load a package every new R session.- You can also use Rstudio to download multiple packages easily and at once.

Tools -> Install Packages

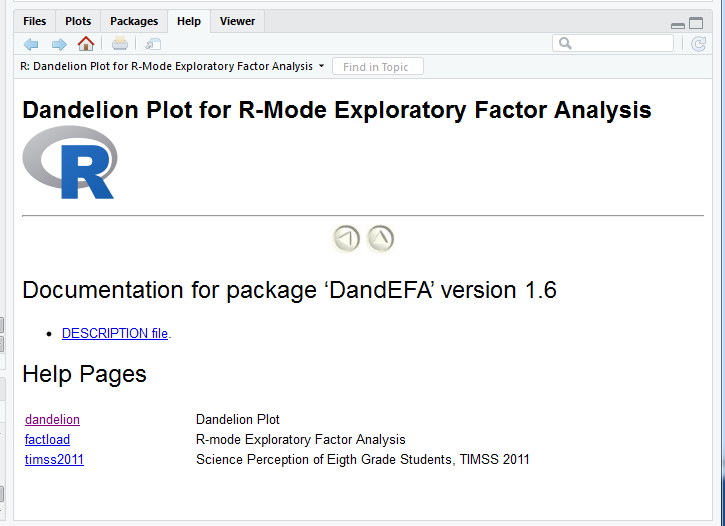

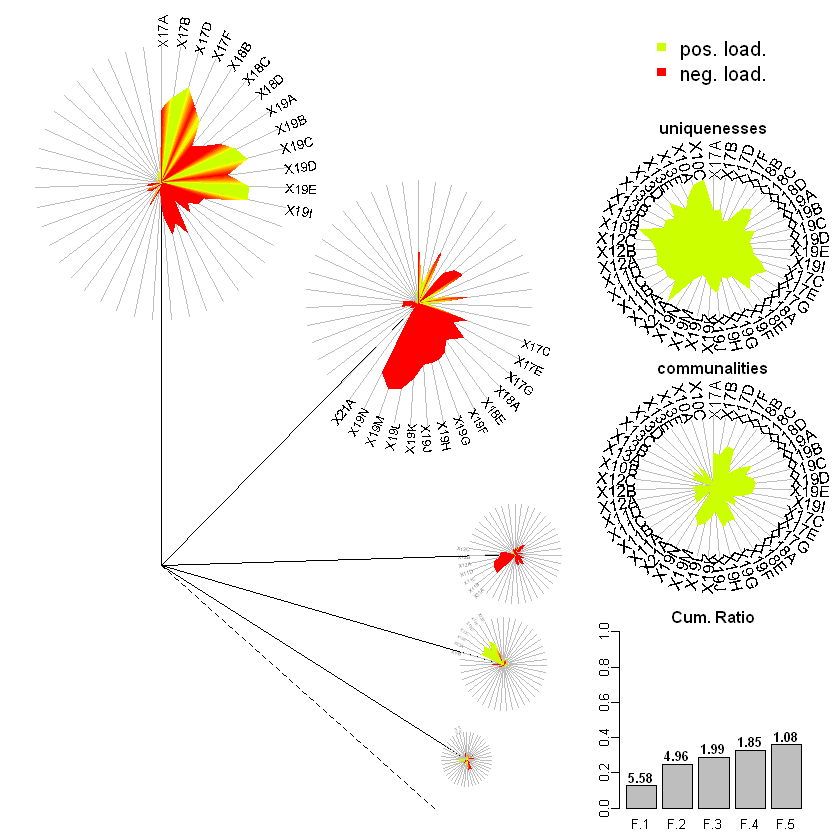

An Example for Packages: DandEFA Package

- Using packages to utilize various methods and algorithms.

- DandEFA package contains functions for a particular analysis called factor analysis.

- Factor Analysis is a method for categorize variables into groups to find the relationship between the variables in the same group.

- The package contains functions:

- factload: A method for producing the factor loadings

- dandelion: A method for visualizing the factor loadings

help(package="DandEFA")

- Alternatively you can also use the bottom-right panel in RStudio to get info on a specific function:

#packageDescription("DandEFA")- You don’t have to understand the following code, but understand that the following code is taken from the documentation from the

DandEFApackage and can be applied directly.

library(DandEFA) # loading the package

data(timss2011) # loading the dataset

timss2011 <- na.omit(timss2011) # removing the rows with missing values

dandpal <- rev(rainbow(100, start = 0, end = 0.2)) # Choose colors for visualisation

facl <- factload(timss2011,nfac=5,method="prax",cormeth="spearman") # Find the factor loadings

facl # Show the factor loadings

dandelion(facl,bound=0,mcex=c(1,1.2),palet=dandpal) # Visualise

Loadings:

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

X10A 0.103 -0.101 -0.224

X10B

X10C 0.106 -0.129

X11A -0.544 -0.130

X11B -0.514

X11C -0.129 -0.105 -0.500

X11D -0.475

X12A -0.116 -0.152 -0.338 0.318

X12B -0.254 -0.133 -0.328 0.256

X12C -0.149 -0.136 -0.298 0.249

X13A 0.549

X13B 0.504

X13C 0.583

X13D 0.398

X13E 0.595

X13F 0.458

X17A -0.539 -0.419 -0.140

X17B 0.633 0.156 -0.164

X17C -0.350 -0.450 -0.185

X17D 0.727 0.222 -0.173

X17E -0.325 -0.337 -0.164

X17F -0.611 -0.445 -0.143

X17G -0.252 -0.481 -0.145 0.157

X18A -0.303 -0.420 -0.267 -0.138

X18B 0.537 0.146 0.152 -0.152

X18C -0.353 -0.326 -0.192

X18D -0.416 -0.413 -0.277

X18E -0.160 -0.381 -0.239 -0.125

X19A -0.540 -0.443 -0.135 -0.254

X19B 0.633 0.119

X19C 0.694 0.158

X19D -0.519 -0.424 -0.163 -0.256

X19E 0.687 0.112

X19F -0.415 -0.462 -0.124 -0.361

X19G -0.313 -0.491 -0.220 -0.359

X19H -0.383 -0.500 -0.214 -0.361

X19I 0.690

X19J -0.238 -0.507 -0.158

X19K -0.620 0.142

X19L -0.714 0.124

X19M -0.749 0.101

X19N -0.184 -0.654

X21A -0.120 -0.106

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

SS loadings 5.576 1.851 4.965 1.987 1.076

Proportion Var 0.130 0.043 0.115 0.046 0.025

Cumulative Var 0.130 0.173 0.288 0.334 0.359

- In summary, packages provide a flexible environment.

- Employing multiple methods and algorithms in the same time

- Programming and using packages are two core elements in R.

Working Directory

- In order to work in R, you should specify a active working directory. In brief this is the location where R will get and save the files.

- You can call the active working directory with the command

getwd() - Note: If you don’t understand the concept of

working directory, you will probably get errors during importing dataset and locating files. So be careful.

# returns path for the current working directory

getwd()- You can change your active working directory either by using

setwd()function or by using Session \(\rightarrow\) Set Working Directory \(\rightarrow\) To Source File Location after saving a script.

# set the working directory to a specified directory

setwd("C:/Users/erhan/Desktop")

getwd()setwd("C:/Users/erhan/Documents/FEF1002")

getwd()Data Types in R Programming

Vectors

- Vectors are one dimensional arrays that keeps only one type of variables.

- All the elements in a vector should be the same type. (Numeric, string, logical etc.)

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7) # Numeric Vector

x- 10.4

- 5.6

- 3.1

- 6.4

- 21.7

x <- c("boy","girl","boy","girl","boy","boy") # character vector

x- 'boy'

- 'girl'

- 'boy'

- 'girl'

- 'boy'

- 'boy'

x <- c(TRUE,TRUE,FALSE,TRUE,TRUE,FALSE) # logical vector

x- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

# or you can use

x <- c(T,T,F,T,T,F) # logical vector

x- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- What if I put different kind of values in a vector.

c(10, 20, 26, T) # numeric and logical values- 10

- 20

- 26

- 1

c(10, 20, 26, "apple") # numeric and string- '10'

- '20'

- '26'

- 'apple'

c(T, F, "apple", "banana") # logical and string- 'TRUE'

- 'FALSE'

- 'apple'

- 'banana'

c(T, "apple", 10) # logical, string, numeric- 'TRUE'

- 'apple'

- '10'

- Accessing elements in a vector is easy,

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7) # Numeric VectorIndexing in R starts with

1opposing to some programming languages like Python which starts indexing with0.Select fifth element of the vector.

x[5]- Select first, third and fifth element of the vector.

ind <- c(1,3,5)

x[ind]- 10.4

- 3.1

- 21.7

- Select second and fourth element of the vector.

ind <- c(F,T,F,T,F)

x[ind]- 5.6

- 6.4

- A logical operation over a vector would create a logical vector (important!!)

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7) # Numeric Vector- Find whether an element is higher than 7.

ind <- (x > 7)

ind- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- Find elements that is higher than 7.

x[ind]- 10.4

- 21.7

- Find elements that is equal or lower than 7.

x[!ind]- 5.6

- 3.1

- 6.4

- We will use indices to manipulate data sets later. But a shorter version of the code is

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7) # Numeric Vectorx[x > 7]- 10.4

- 21.7

- A logical operator checks whether the both sides have equal length or one side has length 1.

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7)

y <- c(4, 7, 8, 2, 35)ind <- (x > y)

ind- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- If the number of elements are not equal:

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7)

y <- c(4,7,8,2)- will give an output but with a warning.

ind <- (x > y)Warning message in x > y:

"longer object length is not a multiple of shorter object length"ind- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

Modifying Vectors

- Any element of the vector can be modified easily:

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7)x[4] <- 7.3

x- 10.4

- 5.6

- 3.1

- 7.3

- 21.7

- A group of elements can be modified too

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7)x[x > 7] <- 100

x- 100

- 5.6

- 3.1

- 6.4

- 100

- Some advance stuff: (data imputation)

x <- c(10.4, NA, 3.1, 6.4, NA)is.na(x)- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

x[is.na(x)] <- mean(x, na.rm = TRUE)

x- 10.4

- 6.63333333333333

- 3.1

- 6.4

- 6.63333333333333

Manipulating vectors

- Merging vectors with c():

x <- c(10.4, 5.6, 3.1, 6.4, 21.7)

y <- c(4, 7, 8, 2, 35)

z <- c(x,y)z- 10.4

- 5.6

- 3.1

- 6.4

- 21.7

- 4

- 7

- 8

- 2

- 35

- Summation or multiplication over vectors. Note: Again both vectors either have be of same size or one has to be of length one.

x

y- 10.4

- 5.6

- 3.1

- 6.4

- 21.7

- 4

- 7

- 8

- 2

- 35

z <- x + y

z- 14.4

- 12.6

- 11.1

- 8.4

- 56.7

z <- x * y

z- 41.6

- 39.2

- 24.8

- 12.8

- 759.5

Generating Sequences

- the colon

:,

x <- 1:10

x- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

x <- 2*(1:10)

x- 2

- 4

- 6

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 14

- 16

- 18

- 20

- the

seq()function.

x <- seq(1,10)

x- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

x <- seq(1,10,by=0.5)

x- 1

- 1.5

- 2

- 2.5

- 3

- 3.5

- 4

- 4.5

- 5

- 5.5

- 6

- 6.5

- 7

- 7.5

- 8

- 8.5

- 9

- 9.5

- 10

- the

rep()function.

x <- rep(3, 10)

x- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

- 3

y <- rep(c(F,T,F,T,T,T),3)

y- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- TRUE

z1 <- rep(c(4,7,8,2,35),each=3)

z1- 4

- 4

- 4

- 7

- 7

- 7

- 8

- 8

- 8

- 2

- 2

- 2

- 35

- 35

- 35

z2 <- rep(c(4,7,8,2,35), times = 3)

z2- 4

- 7

- 8

- 2

- 35

- 4

- 7

- 8

- 2

- 35

- 4

- 7

- 8

- 2

- 35

An Example on Vectors

x <- c(2,4,6,8,10)

y <- c("apple", "banana", "peach", "walnut", "apple")sum(x)sum(x < 6)mean(x < 6)x[x < 6]- 2

- 4

x

y- 2

- 4

- 6

- 8

- 10

- 'apple'

- 'banana'

- 'peach'

- 'walnut'

- 'apple'

mean(y=="apple")mean(x > 6 & y=="apple")Factors

A factor is a special type of vector used to represent categorical data, e.g. gender, social class, etc.

- Stored internally as a numeric vector with values \(1, 2, ..., k\), where \(k\) is the number of levels.

- Can have either ordered and unordered factors.

- A factor with \(k\) levels is stored internally consisting of 2 items.

- a vector of \(k\) integers

- a character vector containing strings describing what the \(k\) levels are.

Factor Example

Five people are asked to rate the performance of a product on a scale of 1-5, with 1 representing very poor performance and 5 representing very good performance. The following data were collected.

- We have a numeric vector containing the satisfaction levels.

satisfaction <- c(1, 3, 4, 2, 2, 3, 4, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 4, 3)- Want to treat this as a categorical variable and so the second line creates a factor. The

levels=1:5argument indicates that there are 5 levels of the factor. We also set the labels for each factor.

fsatisfaction <- factor(satisfaction,

levels=1:5,

labels = c("very poor", "poor", "average","good", "very good"))fsatisfaction- very poor

- average

- good

- poor

- poor

- average

- good

- poor

- very poor

- poor

- very poor

- very poor

- good

- average

Levels:

- 'very poor'

- 'poor'

- 'average'

- 'good'

- 'very good'

Matrices

- Matrices are used for many purposes in R.

- First let’s create a vector from a normal distribution that we will convert to matrix.

set.seed(100) # to ensure the numbers are same for each of you

m <- rnorm(12,0,1)

m- -0.502192350531457

- 0.131531165327303

- -0.07891708981887

- 0.886784809417845

- 0.116971270510841

- 0.318630087617032

- -0.58179068471591

- 0.714532710891568

- -0.825259425862769

- -0.359862131395465

- 0.0898861437775305

- 0.0962744602851301

dim(m) <- c(3,4)

m| -0.50219235 | 0.8867848 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

- or you can specify the dimensions with the

matrix()function

set.seed(100) # to ensure the numbers are same for each of you

m <- rnorm(12)

m- -0.502192350531457

- 0.131531165327303

- -0.07891708981887

- 0.886784809417845

- 0.116971270510841

- 0.318630087617032

- -0.58179068471591

- 0.714532710891568

- -0.825259425862769

- -0.359862131395465

- 0.0898861437775305

- 0.0962744602851301

m <- matrix(m, nrow = 3, ncol = 4, byrow = F)

m| -0.50219235 | 0.8867848 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

- Basic functions on matrices.

nrow()andncol()calls numbers of rows and columns.t()calls the transpose of the matrix.rownames()andcolnames()are the names of columns and rows.

set.seed(100) # to ensure the numbers are same for each of you

m <- rnorm(12)

m <- matrix(m, nrow = 3, ncol = 4, byrow = F)

m| -0.50219235 | 0.8867848 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

nrow(m)ncol(m)colnames(m) <- c("A", "B", "C", "D")

m| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| -0.50219235 | 0.8867848 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

Merging Vectors

rbind()andcbind()functions merges vectors or matrices into matrices.

set.seed(100)

X1 <- rnorm(12)

X2 <- 1:12m <- cbind(X1,X2)

m| X1 | X2 |

|---|---|

| -0.50219235 | 1 |

| 0.13153117 | 2 |

| -0.07891709 | 3 |

| 0.88678481 | 4 |

| 0.11697127 | 5 |

| 0.31863009 | 6 |

| -0.58179068 | 7 |

| 0.71453271 | 8 |

| -0.82525943 | 9 |

| -0.35986213 | 10 |

| 0.08988614 | 11 |

| 0.09627446 | 12 |

Number of columns should be equal for

rbind.Likewise, number of rows should be equal for

cbind.Create two matrices

set.seed(100)

data_1 <- matrix(rnorm(12),nrow=3,ncol=4,byrow=T)

data_2 <- matrix(rnorm(16),nrow=4,ncol=4,byrow=F)- and combine them.

data_new <- rbind(data_1,data_2)

data_new| -0.50219235 | 0.1315312 | -0.07891709 | 0.88678481 |

| 0.11697127 | 0.3186301 | -0.58179068 | 0.71453271 |

| -0.82525943 | -0.3598621 | 0.08988614 | 0.09627446 |

| -0.20163395 | -0.3888542 | -0.43808998 | -0.81437912 |

| 0.73984050 | 0.5108563 | 0.76406062 | -0.43845057 |

| 0.12337950 | -0.9138142 | 0.26196129 | -0.72022155 |

| -0.02931671 | 2.3102968 | 0.77340460 | 0.23094453 |

Indexing Matrices

set.seed(100) # to ensure the numbers are same for each of you

m <- matrix(rnorm(12), nrow = 3, ncol = 4, byrow = F)

m| -0.50219235 | 0.8867848 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

- Extract the first row.

m[1,]- -0.502192350531457

- 0.886784809417845

- -0.58179068471591

- -0.359862131395465

- Extract the second column.

m[,2]- 0.886784809417845

- 0.116971270510841

- 0.318630087617032

- Extract all the rows except the first row.

m[-1,]| 0.13153117 | 0.1169713 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | 0.3186301 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

- Extract all the columns except the first and the third one.

m[, -c(1,3)]| 0.8867848 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.1169713 | 0.08988614 |

| 0.3186301 | 0.09627446 |

index_row <- 1:3

index_col <- c(1,3,4)- Extract the first, second and third row and first, third and fourth column.

m[index_row,index_col]| -0.50219235 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

- or alternatively you can use

m[1:3, c(1,3,4)]| -0.50219235 | -0.5817907 | -0.35986213 |

| 0.13153117 | 0.7145327 | 0.08988614 |

| -0.07891709 | -0.8252594 | 0.09627446 |

Data Frames

A data frame

- can be thought of as a data matrix or data set;

- is a list of vectors and/or factors of the same length;

- has a unique set of row names.

Data in the same position across columns come from the same experimental unit.

Can create data frames from pre-existing variables.

The main spec of data frame is the ability to keep variables with different forms.

Both numeric, string and logical variables can be reserved in a single dataframe unlike vectors and matrices.

Creata a vector called

mean_weight.

mean_weight <- c(179.3, 179.9, 180.5, 180.1, 180.3, 180.4)

mean_weight- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

- 180.1

- 180.3

- 180.4

- Creata a vector called

Gender.

Gender <- c("M", "M", "F", "F", "M", "M")

Gender- 'M'

- 'M'

- 'F'

- 'F'

- 'M'

- 'M'

- Convert

Genderto a factor variable.

Gender <- factor(Gender,levels=c("M","F"))

Gender- M

- M

- F

- F

- M

- M

Levels:

- 'M'

- 'F'

- Combine both vectors into a dataframe.

d <- data.frame(mean_weight, Gender)

d| mean_weight | Gender |

|---|---|

| 179.3 | M |

| 179.9 | M |

| 180.5 | F |

| 180.1 | F |

| 180.3 | M |

| 180.4 | M |

- Note that the resulting variables have different data types.

mean_weightis numeric.Genderis factor.

- This wouldn’t be the case if we try to store them in a matrix as they can only store one type of variable.

Converting other Structures to Dataframes

You can also convert other data types to dataframes

- Converting a matrix to a data frame:

d <- cbind(mean_weight,Gender)

d| mean_weight | Gender |

|---|---|

| 179.3 | 1 |

| 179.9 | 1 |

| 180.5 | 2 |

| 180.1 | 2 |

| 180.3 | 1 |

| 180.4 | 1 |

- We created a matrix from

mean_weightandGender.Genderis automatically converted to a numerical variable as variables in the matrices should be in the same data type.

d <- as.data.frame(d)

d| mean_weight | Gender |

|---|---|

| 179.3 | 1 |

| 179.9 | 1 |

| 180.5 | 2 |

| 180.1 | 2 |

| 180.3 | 1 |

| 180.4 | 1 |

- Even if we convert the matrix to a dataframe the categorical names of the

Genderis gone.

Accesssing elements in a dataframe

- There are a lot of different way to access rows and columns in a dataframe.

- You can either use single bracket

[ ], double bracket[[ ]]or$sign. - Investigate the following code snippets to understand how

Rbehaves.

d$mean_weight # output in vector format- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

- 180.1

- 180.3

- 180.4

d[["mean_weight"]] # output in vector format- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

- 180.1

- 180.3

- 180.4

d[,1] # output in vector format- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

- 180.1

- 180.3

- 180.4

d[,"mean_weight"] # output in vector format- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

- 180.1

- 180.3

- 180.4

d["mean_weight"] # output in dataframe format| mean_weight |

|---|

| 179.3 |

| 179.9 |

| 180.5 |

| 180.1 |

| 180.3 |

| 180.4 |

d[1] # output in dataframe format| mean_weight |

|---|

| 179.3 |

| 179.9 |

| 180.5 |

| 180.1 |

| 180.3 |

| 180.4 |

- You can access a subset of rows by indexing the data frame

d[c(1,4,5),] # Shows 1., 4. and 5. rows of the dataframe| mean_weight | Gender | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 179.3 | 1 |

| 4 | 180.1 | 2 |

| 5 | 180.3 | 1 |

- It is suggested that you use

drop=FALSEwhen indexing (to sustain the data frame type).

d[1:3,"mean_weight"]- 179.3

- 179.9

- 180.5

d[1:3,"mean_weight",drop=FALSE]| mean_weight |

|---|

| 179.3 |

| 179.9 |

| 180.5 |

Creating a new variable in a dataframe

d| mean_weight | Gender |

|---|---|

| 179.3 | 1 |

| 179.9 | 1 |

| 180.5 | 2 |

| 180.1 | 2 |

| 180.3 | 1 |

| 180.4 | 1 |

d$color <- NA

d| mean_weight | Gender | color |

|---|---|---|

| 179.3 | 1 | NA |

| 179.9 | 1 | NA |

| 180.5 | 2 | NA |

| 180.1 | 2 | NA |

| 180.3 | 1 | NA |

| 180.4 | 1 | NA |

d$weight_two_times <- d$mean_weight*2

d| mean_weight | Gender | color | weight_two_times |

|---|---|---|---|

| 179.3 | 1 | NA | 358.6 |

| 179.9 | 1 | NA | 359.8 |

| 180.5 | 2 | NA | 361.0 |

| 180.1 | 2 | NA | 360.2 |

| 180.3 | 1 | NA | 360.6 |

| 180.4 | 1 | NA | 360.8 |

Importing Data

- The most popular functions for reading data sets

read.table()function is used mainly for reading data from formatted text files.read.csv()function is used mainly for reading data from files with csv format (“Comma Separated Values”format)read_excel()function is used to read data directly from an excel file. It requires the external packagereadxl.

Datasets

You can download the datasets used in this lecture from the lecturers AVESIS page.

Pima Data Set

- Indian females of Pima heritage (Native americans living in an area consisting of what is now central and southern Arizona)

- Columns (or Variables) of the Pima data set:

- NTP: number of times pregnant

- PGC: Plasma glucose concentration a 2 hours in an oral glucose tolerance test

- DBP: Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

- TSFT: Triceps skin fold thickness (mm)

- SI: 2-Hour serum insulin (mu U/ml)

- BMI: Body mass index (weight in kg/(height in meter square))

- Diabetes pedigree function:

- Age: Age (years)

- Diabetes: f0,1g value 1 is interpreted as “tested positive for diabetes”

- First, you have to check whether the working directory of R and the location of file matches.

getwd()- The location of the working directory can be changed with

setwd()function. - Alternatively you can change the working directory to the where the Rcode is located with RStudio by using:

Session->Set Working Directory->To Source File Location

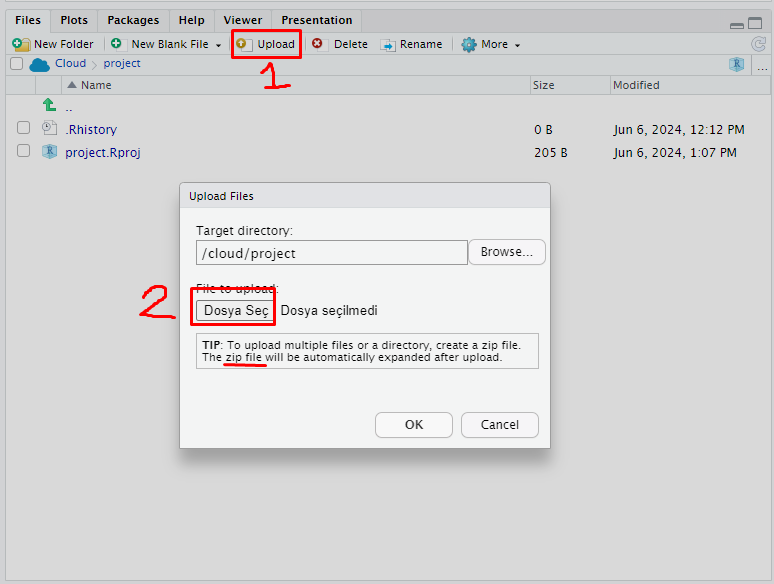

Working on the Posit Cloud

- If you are working on the Posit Cloud you don’t have to change your working directory since you are on the Cloud.

- But you have to upload your datasets to the cloud so that RStudio can locate and use it.

- On the left below pane, click the button Upload in Posit Cloud then a sub menu named Upload Files will emerge.

- Click Select Files from the menu

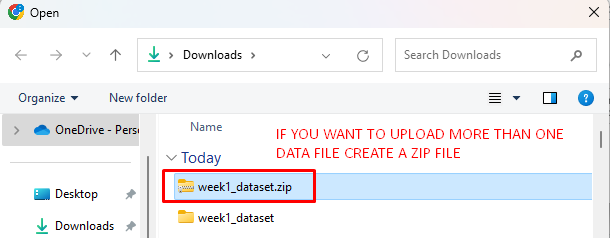

- From the file upload menu select the data files you wish to upload. If you intend to upload multiple files create a zip file from the datasets.

- Posit Cloud will automatically extract it once it uploads the zip file to the cloud.

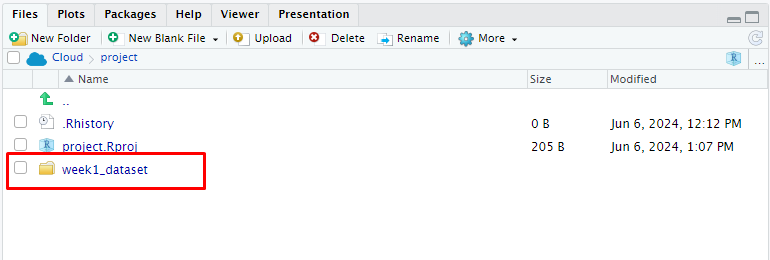

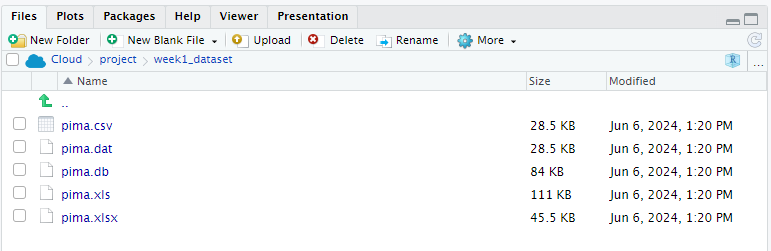

- For example, week1_dataset.zip contains five different data formats for the pima dataset. When it is uploaded all five data files will be extracted under the folder week1_dataset.

- Now you can use the following importing functions inside the Posit Cloud to call dataset into R.

Importing Data from Text Files

- Now let’s check our working directory once more.

getwd()- Now if I want to import any data by using a function with R, I have to either:

- Provide the full location of the dataset inside the function such as:

C:/Users/erhan/Documents/FEF1002/pima.dat - or since my working directory is the folder

FEF1002, if I put mypima.datdata inside theFEF1002folder, it would be sufficient for me to providepima.datas the location.

- Provide the full location of the dataset inside the function such as:

- So in practice both

pima_data <- read.table("pima.dat", header = TRUE, sep = " ")and

You can use the head() function to see if everything is imported okay.

head(pima_data)| NTP | PGC | DBP | TSFT | SI | BMI | DPF | Age | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 148 | 72 | 35 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.627 | 50 | positive |

| 1 | 85 | 66 | 29 | 0 | 26.6 | 0.351 | 31 | negative |

| 8 | 183 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 0.672 | 32 | positive |

| 1 | 89 | 66 | 23 | 94 | 28.1 | 0.167 | 21 | negative |

| 0 | 137 | 40 | 35 | 168 | 43.1 | 2.288 | 33 | positive |

| 5 | 116 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 25.6 | 0.201 | 30 | negative |

- You can use the

str()function to see the structure of the dataset.

str(pima_data)

pima_data <- read.table("C:/Users/erhan/Documents/FEF1002/pima.dat",

header = TRUE, sep = " ")will work and import the data. * Remember to change C:/Users/erhan/Documents/FEF1002/pima.dat to where the pima.dat is actually located. * You can use both approach for the following data importing processes.

head(pima_data)| NTP | PGC | DBP | TSFT | SI | BMI | DPF | Age | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 148 | 72 | 35 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.627 | 50 | positive |

| 1 | 85 | 66 | 29 | 0 | 26.6 | 0.351 | 31 | negative |

| 8 | 183 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 0.672 | 32 | positive |

| 1 | 89 | 66 | 23 | 94 | 28.1 | 0.167 | 21 | negative |

| 0 | 137 | 40 | 35 | 168 | 43.1 | 2.288 | 33 | positive |

| 5 | 116 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 25.6 | 0.201 | 30 | negative |

str(pima_data)'data.frame': 768 obs. of 9 variables:

$ NTP : int 6 1 8 1 0 5 3 10 2 8 ...

$ PGC : int 148 85 183 89 137 116 78 115 197 125 ...

$ DBP : int 72 66 64 66 40 74 50 0 70 96 ...

$ TSFT : int 35 29 0 23 35 0 32 0 45 0 ...

$ SI : int 0 0 0 94 168 0 88 0 543 0 ...

$ BMI : num 33.6 26.6 23.3 28.1 43.1 25.6 31 35.3 30.5 0 ...

$ DPF : num 0.627 0.351 0.672 0.167 2.288 ...

$ Age : int 50 31 32 21 33 30 26 29 53 54 ...

$ Diabetes: Factor w/ 2 levels "negative","positive": 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 ...- Here, the argument

header = TRUEis used to denote that the variable names are given at the first line of the data. - The argument

sep = " "is used to denote how the variables are separated from each other. For this datasetspaceis used to separate variables.

Importing Data From CSV Files

pima_csv <- read.csv("pima.csv", header = TRUE, sep = ",")head(pima_csv)| NTP | PGC | DBP | TSFT | SI | BMI | DPF | Age | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 148 | 72 | 35 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.627 | 50 | positive |

| 1 | 85 | 66 | 29 | 0 | 26.6 | 0.351 | 31 | negative |

| 8 | 183 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 0.672 | 32 | positive |

| 1 | 89 | 66 | 23 | 94 | 28.1 | 0.167 | 21 | negative |

| 0 | 137 | 40 | 35 | 168 | 43.1 | 2.288 | 33 | positive |

| 5 | 116 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 25.6 | 0.201 | 30 | negative |

str(pima_csv)'data.frame': 768 obs. of 9 variables:

$ NTP : int 6 1 8 1 0 5 3 10 2 8 ...

$ PGC : int 148 85 183 89 137 116 78 115 197 125 ...

$ DBP : int 72 66 64 66 40 74 50 0 70 96 ...

$ TSFT : int 35 29 0 23 35 0 32 0 45 0 ...

$ SI : int 0 0 0 94 168 0 88 0 543 0 ...

$ BMI : num 33.6 26.6 23.3 28.1 43.1 25.6 31 35.3 30.5 0 ...

$ DPF : num 0.627 0.351 0.672 0.167 2.288 ...

$ Age : int 50 31 32 21 33 30 26 29 53 54 ...

$ Diabetes: Factor w/ 2 levels "negative","positive": 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 ...- From the code we can understand that column names are included in the data (

header = TRUE) and variables are separated withcomma(sep = ",")

Importing Data From Excel Files

- Remember that you can always use an external package to complete a different task

- Suppose we want to import directly from an excel file with

.xlsor.xlsxformat - We will use the

readxlpackage.

library(readxl) # Remember youj should use install.packages('readxl') if you didn't install it before

pima_xls <- read_excel("pima.xls", sheet = 'pima')head(pima_xls)| NTP | PGC | DBP | TSFT | SI | BMI | DPF | Age | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 148 | 72 | 35 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.627 | 50 | positive |

| 1 | 85 | 66 | 29 | 0 | 26.6 | 0.351 | 31 | negative |

| 8 | 183 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 0.672 | 32 | positive |

| 1 | 89 | 66 | 23 | 94 | 28.1 | 0.167 | 21 | negative |

| 0 | 137 | 40 | 35 | 168 | 43.1 | 2.288 | 33 | positive |

| 5 | 116 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 25.6 | 0.201 | 30 | negative |

str(pima_xls)Classes 'tbl_df', 'tbl' and 'data.frame': 768 obs. of 9 variables:

$ NTP : num 6 1 8 1 0 5 3 10 2 8 ...

$ PGC : num 148 85 183 89 137 116 78 115 197 125 ...

$ DBP : num 72 66 64 66 40 74 50 0 70 96 ...

$ TSFT : num 35 29 0 23 35 0 32 0 45 0 ...

$ SI : num 0 0 0 94 168 0 88 0 543 0 ...

$ BMI : num 33.6 26.6 23.3 28.1 43.1 25.6 31 35.3 30.5 0 ...

$ DPF : num 0.627 0.351 0.672 0.167 2.288 ...

$ Age : num 50 31 32 21 33 30 26 29 53 54 ...

$ Diabetes: chr "positive" "negative" "positive" "negative" ...pima_xlsx <- read_excel("pima.xlsx", sheet = 'pima')head(pima_xlsx)| NTP | PGC | DBP | TSFT | SI | BMI | DPF | Age | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 148 | 72 | 35 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.627 | 50 | positive |

| 1 | 85 | 66 | 29 | 0 | 26.6 | 0.351 | 31 | negative |

| 8 | 183 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 0.672 | 32 | positive |

| 1 | 89 | 66 | 23 | 94 | 28.1 | 0.167 | 21 | negative |

| 0 | 137 | 40 | 35 | 168 | 43.1 | 2.288 | 33 | positive |

| 5 | 116 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 25.6 | 0.201 | 30 | negative |

str(pima_xlsx)Classes 'tbl_df', 'tbl' and 'data.frame': 768 obs. of 9 variables:

$ NTP : num 6 1 8 1 0 5 3 10 2 8 ...

$ PGC : num 148 85 183 89 137 116 78 115 197 125 ...

$ DBP : num 72 66 64 66 40 74 50 0 70 96 ...

$ TSFT : num 35 29 0 23 35 0 32 0 45 0 ...

$ SI : num 0 0 0 94 168 0 88 0 543 0 ...

$ BMI : num 33.6 26.6 23.3 28.1 43.1 25.6 31 35.3 30.5 0 ...

$ DPF : num 0.627 0.351 0.672 0.167 2.288 ...

$ Age : num 50 31 32 21 33 30 26 29 53 54 ...

$ Diabetes: chr "positive" "negative" "positive" "negative" ...- We should define the sheet name of the data with the argument

sheetinside theread_excel()function.